“The long term benefits of sunscreen have been proved by scientists

whereas the rest of my advice has no basis more reliable than my own meandering experience…”— Baz Luhrmann/Mary Schmich.

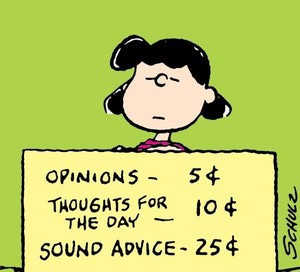

Advice is useful, but it’s not doctrine.

In my writings, I often discuss lessons I’ve learned during more than 30 years in Silicon Valley as a technologist, founder, and investor. Many of these have been hard won through struggle and failure. Hearing perspectives gained from experiences such as mine is valuable, but as its one person’s take, raises the question of how apt it may be in your own, different, case. Comparisons and learnings are not universal. Even when they’re “right,” of which there’s no guarantee, they present only a single perspective. There are always exceptions and caveats. And yet…

I’ve come to view advice offered to me as a gift. To best benefit from it, I try to momentarily put aside skepticism and to understand the point of view being revealed. Once I understand what the advisor is telling me and why they believe it, I can scrutinize and filter at leisure. To get the most value from others’ perspective, I struggle to curb my inclination to fire back with caveats and quibbles, to interject my own perspective, until after I’ve taken in everything I’ve been told, believe I understand their point of view, and have pondered it carefully. If I’m patient enough, I echo back the point of view to ensure I’ve really got the point, and the whole point, that they’re trying to make.

I try to express appreciation for the knowledge they’ve shared.

These listening techniques, Active Listening and Looping are excellent conflict resolution methods. People are much more likely to be able to hear your reactions and perspective after they feel they have been heard and understood.

Gary Friedman and Jack Himmelstein invented the field of mediation, and articulated these methods in their 2008 book, Challenging Conflict: Mediation Through Understanding. In her recent book High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out, Amanda Ripley tells the story of how even Gary Friedman, the father of conflict resolution, found himself engaged in no-win, conflict-enhancing behaviors during a fraught, political standoff in tiny, idyllic Muir Beach California.

Which just goes to show how difficult it actually is to listen well!

Still, invariably, when the conclusions I’ve come to on my own are challenged, I find reasons why those conclusions are wrong or don’t apply to me .

As founders, we have — and need to have — strong biases about our mission that help us conquer the inevitable barriers in our path and focus single-mindedly on succeeding. The resilience of thought we develop in the startup battle becomes second-nature and can get in the way of considering points of view different from our own. Though this doggedness is paramount for maintaining focus and determination, it’s important to be able to quiet it occasionally long enough to consider alternate viewpoints. There’s a difference between being swayed and changing course every time one talks to someone with a new opinion, and allowing for moments of opening mental space to different perspectives if only long enough to ensure we aren’t heading into an unforeseen trap. Unless we do this, we not going to learn from those who went before us, and are going to make the same expensive mistakes ourselves.

Sometimes an outside opinion opens up a new way of thinking about our challenges and helps us avoid pitfalls. Sometimes it doesn’t apply to us. But, we all have strong confirmation biases which skew us to seeing only evidence of our own pre-established beliefs. If we repeatedly find reasons why others’ experiences aren’t relevant, why “this time it’s different,” it’s a sign that we need to redouble our efforts to be open-minded.

Of course, not all advisors are the same. As a founder, your time is a scarce resource, so filter carefully who you listen to to begin with. They don’t need to be just like you, you need to also understand the experiences of people who have trod different paths, but only spend time with people whose approach you respect, who are experienced, and who are epistemologically aligned with you. If they don’t share your world view in a broad sense, their goals will likely not be the same either, and their advice probably doesn’t apply to how you’ll act anyway.

Adam Grant has an interesting piece in the New York Times “We Get, and Give, Lots of Bad Advice. Here’s How to Stop”, which discusses how to choose advisors, types of advisor bias, Solomon’s paradox (we are wiser about other people’s situations than our own), and tips on how to give yourself advice:

… psychologists find that our reasoning becomes wiser when we think about our own problems from a third-person perspective.

And, while we’re on the subject of how advice isn’t always perfect, if you are going to take the advice I offer in the title of this story and wear sunscreen, make it coral reef friendly.

Marc Meyer is a long-time Silicon Valley technologist, founder (6 startups, 4 exits, 1 IPO), executive, investor, advisor, teacher and coach. He has invested in and advised over 100 companies, chairs the Advisor Council at Berkeley SkyDeck, is on the Selection Committee of HBS Alumni Angels, advises at multiple accelerators, and has an Executive Coaching practice helping leaders achieve their greatest potential.

A previous version of this article appeared on Medium.